These Morehouse students participated in the joint Race and Law class: (L-R) Trenaj Mongo, Deonté T. Mayfield, Walker Hill, Jeremiah A. Davis, KeAndre Pippens, Grant Alexander/Photo by Morehouse Professor Winfield Murray

By Deonté Mayfield ’22, Staff Writer

“Once a person is labeled a felon, he or she is ushered into a parallel universe in which discrimination, stigma, and exclusion are perfectly legal.”

— Michelle Alexander in her book “The New Jim Crow”

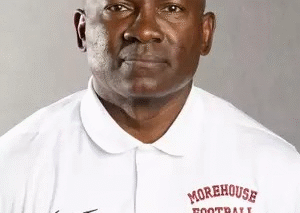

Professor Winfield Murray of Morehouse College teaches a Race and Law class inside a “parallel universe” to those incarcerated at a correctional center in South Georgia. The students in his class are on track for their associate degrees.

Murray’s class is taught to recognize how racial bias or bias in general has been used in policy making and courts of law.

On April 8, Murray selected a few students from Morehouse to participate in a joint class session with the students of the correctional center. To protect the relationship between Common Good Atlanta (an organization that provides current and previous incarcerated people access to higher education) and the correctional center, its name and the last names of the inmates will be omitted in this article.

Excitement was in the air on the road to this “parallel universe.” Everyone seemed eager to engage in discussions with the 15 inmates of Murray’s Race and Law class. Upon arrival, the inmates gave out “handshakes” and “daps” with a warm welcome.

The parallel aspect of this universe is that Murray was the instructor and everyone else was the student. The students connected instantly with each other, and the atmosphere was set.

Murray opened the Socratic lesson with a question, “What do we think of our jury today?” Hands instantly raised not only from the Morehouse students, but also the incarcerated students. A student from the correctional center, Mark said, “For some it does work, and for some it does not.”

From there the discussion went deeper about the economic class difference and media persuasion that influences the jury and its verdict. The lesson shifted to the professor’s Voir Dire exercise with the class.

Voir Dire is a technique for a line of questioning used by attorneys in a selection of the jury pool.

For the exercise, Kaden and Elijah were my partners as we pretended to vet potential jurors in 1994 before the famed O.J. Simpson murder trial occurred. The group had to create questions to present before the jury pool from the standpoint of the defense counsel for Simpson and the prosecution against him.

“Voir Dire is the best weapon in your arsenal,” Murray said. “It filters out those biases.”

The exercise was a bonding moment for all the students, regardless of their present universe. Kaden and Elijah both wrote and spoke their questions to the mock jury pool full of their peers. One could see the enthusiasm on their faces as they acted as attorneys, not inmates.

Even in this universe time can fly, as it soon was time for us to leave. “Hugs” and “daps” were exchanged with compliments like, “Y’all are historical figures” because we were the first Morehouse students to participate in a joint class at the center. It was a humbling experience to sit across from an inmate and learn about the law as parallel students.

Upon departing, the warden of the South Georgia prison thanked us for the visit. A moving visit it was, but now it was time to take what was learned in this universe and share it with the world.