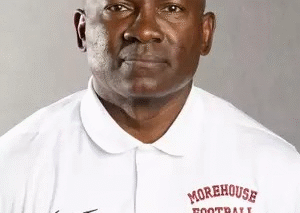

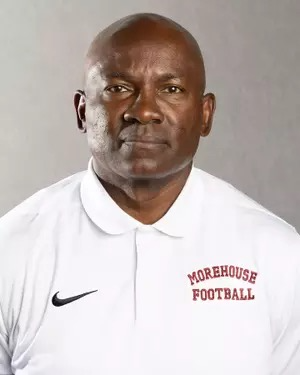

Ron Thomas, Adviser

At a time when it’s rare for an NBA team to draft a player from an HBCU and black-college teams are deep underdogs during March Madness, it’s easy to forget that into the 1980s HBCUs contributed many historically significant and outstanding players to the sport of basketball.

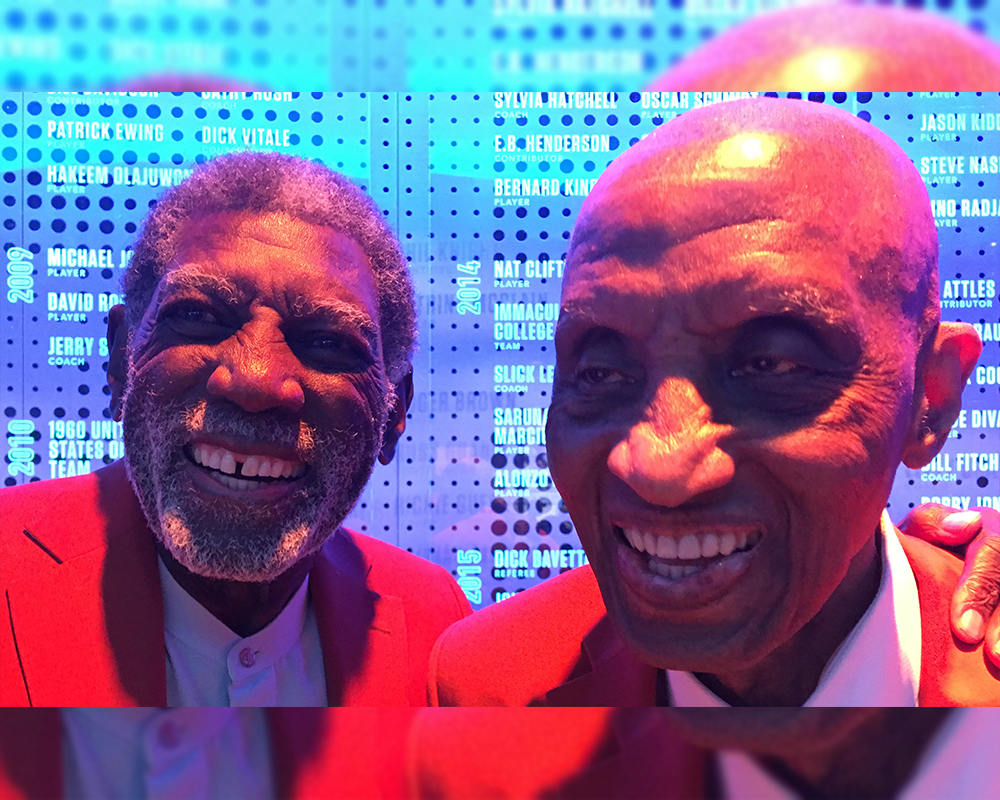

Two impactful former NBA players with HBCU roots, Chuck Cooper and Al Attles, along with the entire Tennessee A&I (now Tennessee State) teams from 1957-59, were inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame on Sept. 6. Former Tennessee A&I star Dick Barnett represented his teammates during the weekend’s events.

The enshrinement ceremonies took place that evening in Springfield’s Symphony Hall, and the day before inductees received their orange Hall of Fame jackets before they were interviewed at the annual press conference.

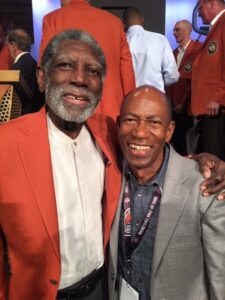

Attles now is in his 60th season with the Warriors as a player from 1960-71, head coach from 1969-83 (including winning the 1975 NBA title), general manager, and overall team ambassador.

He joined the then-Philadelphia Warriors as their fifth-round draft pick in 1960 after leading North Carolina A&T to two consecutive conference titles.

Attles said that black players from HBCUs proved false the myth that if a player didn’t go to a predominately white college, he couldn’t be equally talented. He credited his success in life to his A&T coach, Cal Irvin, who told his players that it was fine to be proud of what they accomplished as athletes, but more important was “that they do more for the people who come behind them,” Attles said.

In 2015, Attles’ No. 22 became the first basketball jersey number retired by A&T. Ironically, the university’s chancellor, Harold Martin Sr., is the father of Morehouse’s interim president in 2017, Harold Martin Jr. ’02.

Barnett was the star of the Tennessee A&I Tigers when they won the small-college NAIA national championship three consecutive years, from 1957-1959. They were the first black-college team to win an integrated national basketball title in history and were coached by John McLendon, himself a member of the Hall of Fame.

Fueled by McLendon’s relentless fast-breaking offense, Barnett was a scoring terror. A 6-foot-4, left-handed shooting guard, he was known for tucking his legs under him and calling out “Fall Back, Baby” as he took jump shots. That’s because he was so sure his shot was going in that he reminded his teammates to fall back on defense. He won the MVP award during A&I’s last two NAIA tournaments.

He was the Syracuse Nationals’ first-round draft pick in 1959, starting a 14-year NBA career in which he averaged 15.8 points per game, played in one All-Star Game and helped win ? NBA titles. His pro career fulfilled Barnett’s boyhood commitment to “my mistress” called basketball, exemplified by what he did during his senior prom in Gary, Indiana.

While 350 of his classmates attended the prom inside their school, Barnett stayed outside on the school’s basketball court, working on his jump shot. When the prom ended at about 10 p.m., he was still there.

“As the last limousine pulled away and as the darkness began to consume me, I still felt sanguine, which means optimistic, because I felt my dream and I, we had a rendezvous with destiny,” Barnett said during the Hall of Fame press conference.

Cooper was posthumously selected by the Direct-Elect Early African-American Pioneers Committee for being the first black athlete drafted by an NBA team. That occurred on April 25, 1950, when Boston made him the first pick of the second round. The 6-foot-5 forward had been an All-American at Duquesne University, but he had begun his college career at West Virginia State, an HBCU, before serving in the Navy during World War II.

Boston drafted him after the NBA had played its first four seasons under a secret ban against black players. Earl Lloyd with Washington, the Knicks’ Nat (Sweetwater) Clifton and the Tri-Cities Blackhawks’ Hank DeZonie also integrated the league in 1950.

After he joined the Celtics, Cooper felt frustrated that his scoring potential was not maximized because he believed teams did not want black players to be star performers. Cooper also felt discriminated against when he was segregated from his white teammates at hotels and restaurants when their teams played in the South.

Celtics owner Walter Brown and coach Red Auerbach tried to ensure that Cooper would not be separated from his teammates from 1950-54, although sometimes they couldn’t prevent it. But the managements on the Hawks’ and Pistons’ franchises he later played for did not care as much about the racism he endured.

Cooper, who died in 1984 at 57, was represented by his son, Chuck Cooper III, at the Hall of Fame ceremonies.

“I’m the same age as he was when he passed away,” his son said. “So it’s like a major milestone, and now I realize just how young that was.”

Chuck Cooper III said that because his father was not a star, his dad couldn’t complain much about the racism he faced. So his father was extremely proud that the NBA’s first black superstars, Bill Russell and Elgin Baylor, were outspoken against racism, and Chuck III called the NBA’s Adam Silver “the greatest commissioner in the world” for letting NBA players express their views about social injustice.